My Education in Racial Superiority

(If you'd prefer to read this as a web page rather than an email, then head on over to HBowie.net.)

First things first: I am, to all appearances, white, and my ancestry, as far as it can be determined, is mostly European.

But please don’t hold that against me.

I grew up in the city of Annapolis, in the state of Maryland, over the course of the sixties. My first year in high school was also the first year of school integration in that region.

And I can’t, in all honesty, say that I paid much attention. There weren’t any demonstrations, there wasn’t any uproar. I did not grow up in a household that paid much attention to politics, or to the great social issues of the day. I was a great reader, and mostly consuming science fiction at that point. There were certainly people of color in our community, but I didn’t really think much about issues related to the colors of our skins.

But I had also developed a great love for much of the rock music of the era, including the Beatles, the Stones, the Who, and, a bit later, Cream. All white bands of course.

But then things began to shift for me towards the end of the sixties, and the beginning of the seventies.

First, because many of my favorite bands, and favorite musicians, began to openly credit the original sources for much of their music: and these were all black musicians.

And then, there was Jimi Hendrix, who was clearly the preeminent rock guitarist of his generation, as well as a powerful songwriter and singer.

And then I began to read Rolling Stone magazine pretty faithfully, and during those years that journal was regularly featuring blues and jazz artists, in addition to the rock groups that had originally sparked our mutual interests.

And then I attended the University of Michigan. I was fortunate to be able to attend a couple of the Ann Arbor Blues Festivals presented there. As Jim O’Neal wrote in Blues in Black and White: The Landmark Ann Arbor Blues Festivals: “The Ann Arbor Blues Festival was the coronation of the blues roots that sired rock to begin with.”

And then the library in my dorm at Michigan allowed me to listen to many blues recordings to which I would not otherwise have had access.

And I had a chance to see B. B. King in concert.

And then there was Miles Davis.

At this point I knew next to nothing about jazz.

But there he was one day on the cover of Rolling Stone, with a review of his latest album, In A Silent Way, included inside.

And I bought the album. And was entranced. (And still am, to this day.)

And then I had a chance to see Miles in concert, at Hill Auditorium, with many of the same band members who played on In A Silent Way. White and black musicians but with Miles, the leader, clearly in charge, even when he had his back turned to us, and wasn’t playing a note.

And I’ve been listening to Miles Davis, and other jazz greats, ever since.

And so now, when I consider a literal pantheon of black singers, composers, songwriters, players and band leaders — Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Muddy Waters, John Coltrane, B. B. King, Robert Johnson, Chuck Berry, Jimi Hendrix — to name just a few — as well as black authors such as Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin and Octavia Butler — I know that my life would be immeasurably poorer without having had a chance to experience their originality and artistry.

I recently came across the following quote (emphasis mine) from Will Durant, in his book The Lessons of History, and I think this sums up my position on racial differences rather nicely:

“Racial” antipathies have some roots in ethnic origin, but they are also generated, perhaps predominantly, by differences of acquired culture — of language, dress, habits, morals, or religion. There is no cure for such antipathies except a broadened education. A knowledge of history may teach us that civilization is a cooperative product, that nearly all peoples have contributed to it; it is our common heritage and debt; and the civilized soul will reveal itself in treating every man or woman ... as a representative of one of these creative and contributory groups.

I like to think that my soul has become rather civilized over the years, and that is certainly due to a rich heritage that counts many black artists among its contributors; and I hope that this piece helps in some small way to pay down some of the debt that is owed on that account.

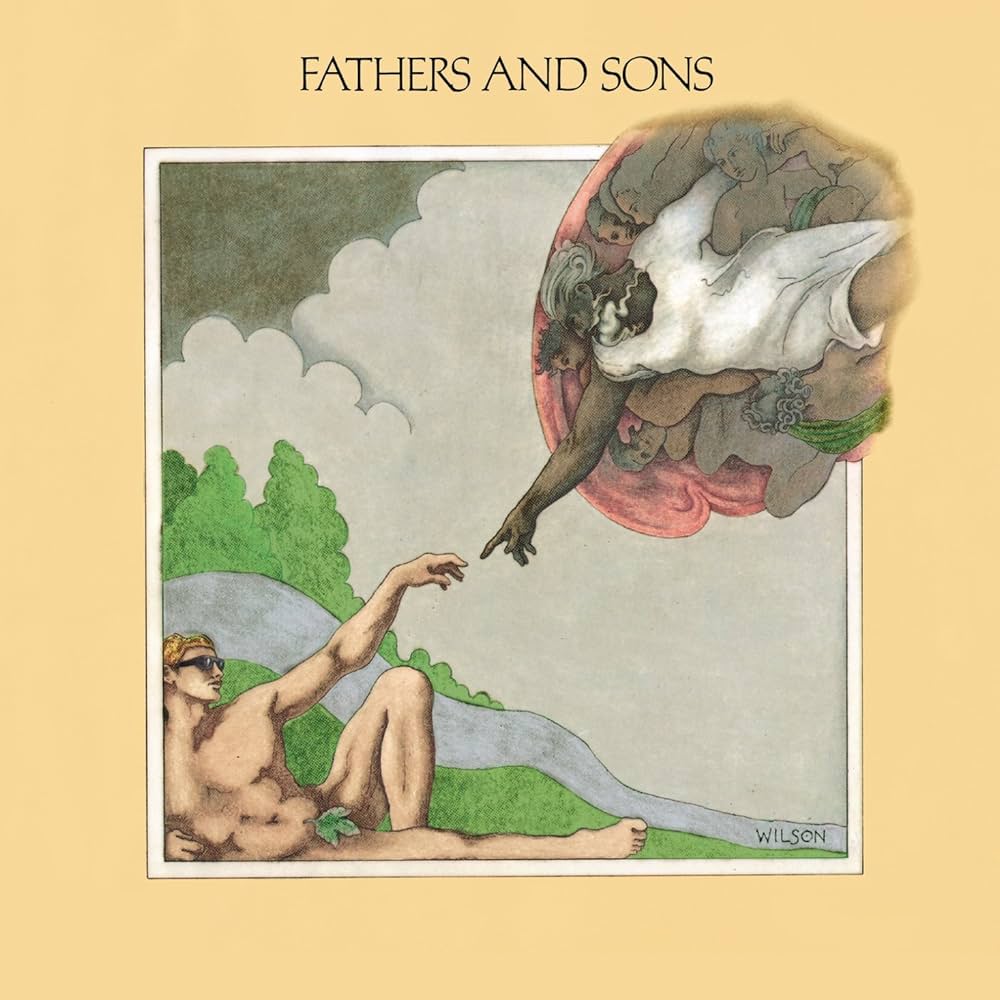

The image at the top of this post is from the wonderful Muddy Waters album, Fathers and Sons, which featured white boys Mike Bloomfield, Elvin Bishop and Paul Butterfield supporting the featured artist, and clearly — as the album cover so faithfully depicts — paying their respects to one of the acknowledged masters, one they had been studying and learning from for years, and without whom they would never have become the musicians they then were.

That album, and that album cover, have stuck with me for over fifty years, and the image for me still portrays an enduring truth.

And so, while I’m not inclined to put stock in any supposed racial superiority, I have to confess that, if I were to lean one way or the other, it would have to be in a direction that would include the many black artists who have contributed so much to my own broadened education.

To do anything else would be to simply fly in the face of so much clear recorded evidence.

I am happy to make all of my content free for anyone to read and share, without any fees, personal data collection, advertising, or restrictive copyrights.

But if you would like to express your appreciation for my work by making a small financial donation, then all gifts will be gratefully accepted!

Clicking on the link below will take you to a page on the Ko-fi site, where you can "buy me a coffee," if you'd like.

Thanks for reading!